Life on Earth is an intricate tapestry woven from billions of years of change, adaptation, and survival. At the heart of this grand story lies speciation — the evolutionary process that gives rise to new species. This phenomenon is not merely a relic of the past but an ongoing, dynamic force shaping biodiversity around us every day.

TLDR (Too Long, Didn’t Read)

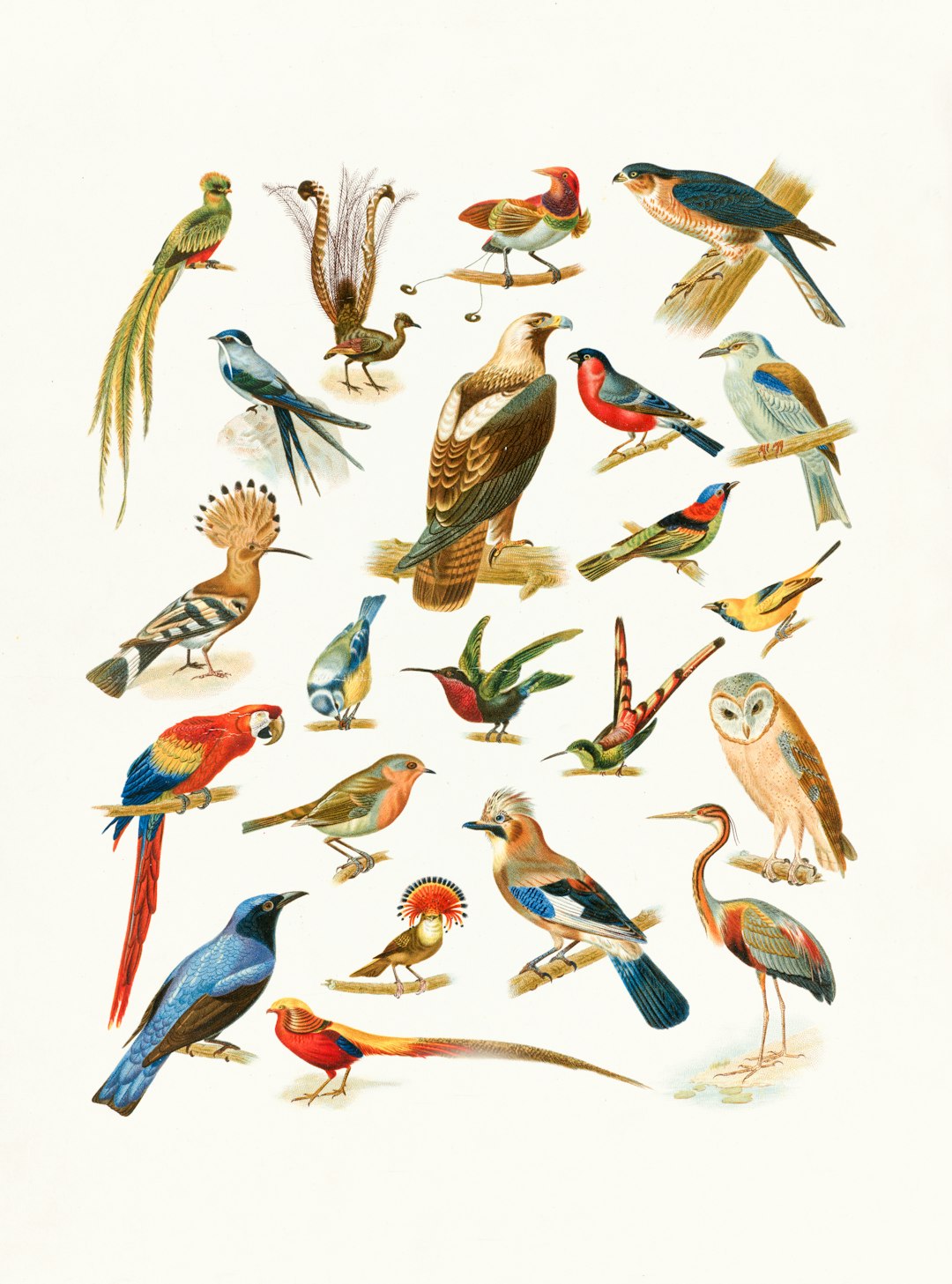

Speciation is the process by which new species evolve from existing ones, a driving force behind the immense variety of life on Earth. It occurs when populations of a species become isolated and gradually diverge due to genetic, geographic, or behavioral changes. Whether it’s birds adapting to new islands or microbes in a petri dish, life constantly finds ways to split, specialize, and thrive. Understanding speciation helps us grasp the fragility and richness of ecosystems in a changing world.

What Exactly Is Speciation?

Speciation is the formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution. It occurs when a group within a species diverges enough genetically and behaviorally that they can no longer interbreed with the original group, even if they come back into contact.

This process can happen in many ways, and scientists categorize speciation into several primary types:

- Allopatric Speciation: When species are geographically separated — think of a mountain rising or a river forming — they evolve along different paths.

- Sympatric Speciation: Occurs without physical barriers. This can happen through behavioral changes, mutations, or exploiting different ecological niches within the same area.

- Peripatric Speciation: Similar to allopatric, but it involves a smaller population that becomes isolated and evolves more rapidly.

- Parapatric Speciation: Adjacent populations evolve into distinct species while maintaining contact along a border region.

Though the mechanisms differ, the outcome is the same: new life, adapted to new circumstances.

The Invisible Hand of Natural Selection

The engine driving speciation is evolution by natural selection, a concept introduced by Charles Darwin. He observed that slight variations between individuals could lead to significant differences in survival and reproduction over generations. When populations are separated or begin to exploit slightly different ecological roles or niches, they face different selective pressures, leading to divergence.

Imagine a population of birds becoming separated by a storm, ending up on different islands. Initially, they are similar. But one island may have insects hidden in bark, and birds with stronger beaks survive and reproduce. Another island may have fruit, favoring birds with longer beaks. Over time, these differences accumulate, and the populations become reproductively isolated. Voilà, two species from one.

Case Study: Darwin’s Finches

No discussion of speciation is complete without mentioning Darwin’s finches. The Galápagos Islands are home to several finch species descended from a common ancestor. They evolved different beak shapes and feeding strategies depending on their specific habitats. From cracking nuts to sipping nectar, their adaptations fueled their divergence.

By studying these finches, Darwin was able to develop the theory that small changes over time could lead to entirely new species. These birds remain one of the best examples of adaptive radiation — a process where a single lineage rapidly diversifies into multiple forms based on environmental opportunities.

The Genetic Side of Speciation

Behind every outward difference lies a genetic story. As populations diverge, so do their gene pools. Mutations accumulate, genes may be lost or gained, and regulatory networks evolve. Modern genetic techniques allow scientists to peer into genomes and even witness speciation in real time.

One particularly fascinating case involves host races — populations of insects that become tied to specific plants. For example, the apple maggot fly in North America has begun splitting between flies that prefer hawthorn and those that prefer apples. Though physically they look the same, their genes are beginning to inch toward isolation.

Environmental Change = Evolutionary Opportunity

Nature does not like a vacuum. When an environment changes — due to climate shifts, tectonic activity, extinction events, or human disturbance — new niches open up. This provides the raw materials for evolutionary experimentation. Some lineages perish, others adapt, and some blossom in unexpected ways.

After the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, mammals boomed. In that vacuum, previously suppressed lineages exploded into a wide variety of forms, from whales to bats to primates. Environmental disruption, while tragic, often paves the way for new speciation events.

Even today, climate change is influencing evolutionary trajectories. Arctic species face new migrants as warming draws southern species northward. Different ranges mean new interactions and, in time, perhaps new species.

How Fast Can Speciation Happen?

While we often think of evolution as glacially slow, speciation can occur quite rapidly under the right circumstances. In laboratory conditions, bacterial species have been documented evolving new forms within years. In the wild, cichlid fish in East African lakes have radiated into hundreds of species in mere thousands of years — a blink of an eye in geological time.

Speed depends on several factors:

- Generation time: Species with shorter life cycles evolve more quickly.

- Mutation rates: Higher rates can introduce variation faster.

- Selective pressure: Stronger environmental differences accelerate divergence.

- Population size: Small populations can shift more quickly due to genetic drift.

Human Influence on Speciation

Humans aren’t just passive observers of evolution — we actively shape it. By altering habitats, introducing invasive species, and even through selective breeding, we’ve become agents of speciation.

One dramatic example is urban speciation. Animals like pigeons, rats, and even insects are adapting differently in cities compared to rural areas. Their reproductive and feeding behaviors are shifting in ways that may, over time, drive them apart genetically.

On the flip side, human activity can also halt or reverse speciation. By reducing habitats and mixing once-isolated populations, we risk blending lineages that were evolving separately, thereby reducing biodiversity.

Why Speciation Matters

Speciation is the wellspring of life’s diversity. Every plant, animal, and microbe exists because of this process. Without it, Earth would be home to far fewer forms of life, and ecosystems would lack resilience.

Understanding speciation isn’t just academic. It helps to:

- Inform conservation: Protecting threatened species means understanding how they evolved and how fragile their uniqueness may be.

- Combat disease: Pathogens can speciate quickly, as seen with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and evolving viruses.

- Appreciate biodiversity: Knowing how life arose enhances our understanding of its worth and intricacy.

Conclusion: Change Is the Only Constant

Speciation shows us that life is not static. It is a story always in motion, adapting and branching like a tree whose limbs stretch into the unknown. Whether through the slow divergence of ancient reptiles or the rapid evolution of urban insects, it reminds us of nature’s incredible creativity and resilience.

As we face an uncertain future marked by rapid environmental shifts, the lesson of speciation — that life finds a path, even through disruption — is both a comfort and a warning. We are part of this ongoing story, and our actions today could shape what life looks like tomorrow.